Go back to go forward

I’ve been mulling over our visit to the National Archives.

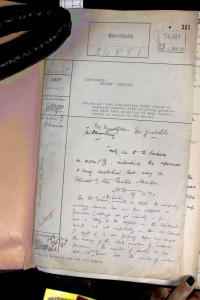

The item that I investigated was an online one, a document circulated by the Home Secretary regarding concerns that unrest in the United States will spread to the UK.

(Item: CAB 24/89/89 Unrest Amongst The Negroes 7th October 1919)

The League for Democracy in the US is composed of negro officers and enlisted men who served in France during the war, the Home Secretary reports. It is an “organisation dedicated to the Negro cause”. A chilling appendix to the document details the names of agitators, including Marcus Garvey.

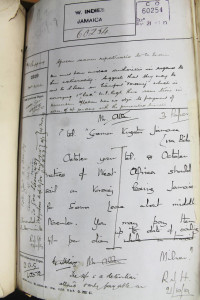

The report goes on to detail unrest in the British Colonies, with particular reference to disturbances in British Honduras and Jamaica. Rioting is rife with discharged coloured soldiers and sailors: “Their slogan is “Kill the Whites”. This counterblast to the riots in Cardiff and Liverpool is a powerful one. The anxiety is spreading.

Immersed as I am in this narrative as it unfolds in the National Archive, I am pulled up short by the process of uncovering such stories. These (his)stories won’t be found with search terms such as “Black Sailors” or “Commonwealth Soldiers”. They are cloaked under search terms that unsettle me. Search terms that this keyboard does not know. Search terms that I wouldn’t think to try because they are not part of my vocabulary.

Negro.

Coloured.

Perhaps it’s a simple, obvious thing – we need to use the vocabulary of the time – but I don’t like it. In the very activity of researching, I am confronted by the very core of this project – difficult histories, national identity and empirical past. I am implicated. I have to go back to go forward.

Helen Bendon Senior Lecturer, Film.